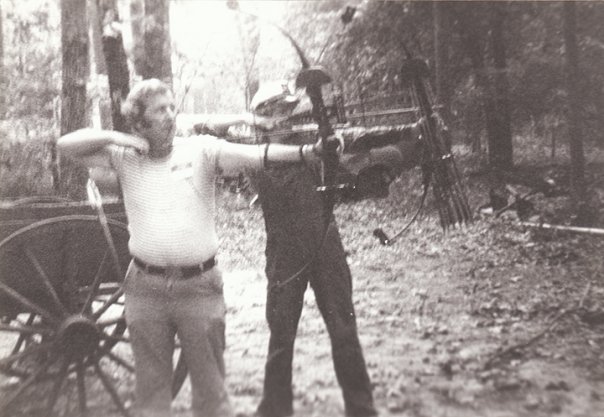

Being raised as my father’s only son I received membership to a certain world my sisters tended to have less access to. Although folks like me from the Deep South don’t particularly like the stereotypes the outside world tends to use when portraying us in entertainment media there are definitely traditions and practices unique to our culture that I suppose feeds the imagination of fancy pants northerners and Hollywood types. I was born in Atlanta in the late 1950s into a world that very nearly doesn’t exist today. I was a very typical southern boy with an even more typical southern father. My dad was the Great Outdoorsman. He was the Southeastern Champion of the National Field Archers Association, president of the Georgia Wildlife Federation, founder of the Georgia Bowhunters Association, a national field representative for Ben Pearson Archery, as well as Zebco fishing equipment, Bagley Bait Company, Mann’s Bait Company, and a few other fishing products. He was personal friends with big named sportsmen like Bill Dance, Rowland Martin, Tom Mann, Orlando Wilson, Howard Hill, Owen Jeffery, and Dan Quillian, just to name a few. All of whom I had the pleasure to meet.

My father was bigger than life to me throughout my childhood. I walked in his shadow everywhere he went. I mimicked his every action. From the time I was two or three years old I would stand out in the yard with him when he was shooting his bow, standing next to him shooting my imaginary bow. Then walking with him to the target and pulling each of my imaginary arrows out one at a time. I finally got my first Browning recurve bow when I was four years old. Before the end of the year I was shooting in an exhibition at the Atlanta Boat Show, popping balloons from 20 paces for the crowd.

Little by little I became more involved in my dad’s universe. I began fishing with him at Brown’s Lakes in South Fulton County when I was three years old way before he found his way into the spotlight as a professional bass fisherman. By the time I was eight or nine years old he gave me a Daisy BB gun. By the time I was twelve I was shooting his 35-caliber deer rifle. You see, when you were a boy in the Deep South in the sixties and seventies guns were as natural to your existence as your blue jeans and your pocketknife.

As I grew up my archery skills grew too. We were members of the Tomochichi Archery Club in Griffin, Georgia and I began to compete. My dad handed me over to Lt. Col. Milan Elott, who ran the Archery College in College Park, Georgia. With the Colonel’s help I eventually won the silver medal in the NFAA Georgia State Freestyle Championship. However, the biggest advance for me in my dad’s universe is when I started going to the deer hunting camps with him.

For years our regular camp was always at the Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge in Jasper County. Then there was the big hunt that happened once a year at Clarks Hill in McDuffie County. We also hunted in Green County and on some land in Polk County, and for a brief time at a hunting camp called Kapow somewhere south of Henry County. But the big camps where my best memories come from were Piedmont and Clarks Hill, which frankly we all called Clark Hill.

Although I had met many of my dad’s friends when they would come over to our house, or on an occasional visit to theirs, it wasn’t until we all gathered at the hunting camps that I really got to know them. I forgot to mention my dad was also a very skilled taxidermist. Our basement was like a mad scientist’s lab, which for me was the coolest thing in the world, but my mother hated it, and my sisters could not handle the dead animals and skulls, and snake skins, and pelts, and glass eyeballs. It was freaking awesome! Anyway, as I was saying this is what would bring my dad’s hunting buddies to our house on occasion. I grew into adulthood around these guys between the ages of 12 and 20. They had wonderful, colorful nicknames. There was Groucho (Lewis), Shorty (Lamar), Smitty (Eugene), Boney Maroney (Buddy), Punkin (my uncle Lamar), and those without nicknames like my dad, Richard, my other uncle, Paul, and Tim, who was Smitty’s best friend. There were others, but these guys were the ones I saw as the core group.

These were hilariously funny and vulgar men. Mostly men of the Korean War. They had jobs that spread the gamut from auto mechanic to CEO of a power company. They were good men. They were brothers, and they all stayed friends until the end. Today, Punkin and Tim are the last ones who remain living. Tim’s daughter is the nurse practitioner with my primary care physician and she has told me how lonely her father feels today, especially after the loss of Smitty. I can still remember how upset my dad was when Groucho, who was the first to go, passed away.

We would sit around the campfire at night and my dad and I would listen to their crazy stories. I would laugh until my sides hurt. My dad was always quiet and was more into listening to the other guys’ stories. He would occasionally remind one of them of something to get them started, but he himself wasn’t really one of the story tellers. He sure loved those guys though, and he would laugh as hard as me on those nights. My dad’s reputation with the gang was really interesting. They all knew he was the best marksman in the group, but he was also the true Boy Scout in their pack as well. My dad was the good kid who loved hanging out with his rascal friends. Dad was a known authority when it came to the ethics of hunting. He was vehemently opposed to poachers and campaigned heavily against them when he was president of the Georgia Wildlife Federation. He played by the rules and the rules mattered.

I helped my dad drag a fair share of deer out of the woods, and I became very good at tracking them. In fact, I loved tracking. Truth be told, I loved everything about hunting but hunting. This is where I should point out that I have never killed a deer. However, before you think I’m a goody two shoes you should know I killed my share of squirrels, birds, and rabbits in my earlier days. I should also say I wanted very badly to kill a deer during most of those years and twice shot and missed. Which is strange for a person who is as good a shot as me. It wasn’t buck fever that caused me to miss either. If anything, it might have been apathy. Some years after my last bow hunt down on Herman Talmadge’s property, when I missed an eight-point buck from a wide-open broadside position only 20 yards out, I began to reflect on that day. That was my last hunt, now 40 years ago. I know my dad would have been so proud if I had taken that deer. I really wanted that for him. And that’s when it truly hit me. I never wanted to kill a deer. I didn’t even want to kill those poor squirrels before that. What I wanted more than anything was to be the kid I thought my dad wanted me to be.

The beauty of my father was in the end it didn’t matter to him. It was me putting the pressure on myself, not him. My dad’s unconditional love did not need a sacrifice at the altar of his ego. This realization was a massive liberator for me. Consequently, I have never questioned my father’s love for me, and he was proud of me for damn near anything I ever did. My dad was far from a perfect man, he might not have even been a perfect father, but his love was authentic, and in that respect nearly as perfect as any love I have known.

Only a few years prior to his death, when the early effects of Alzheimer’s were only beginning to show, we were having dinner at a barbeque house nearby. We were there with some other family members, but my dad was sitting closest to me that night. Somehow the subject of hunting came up. When it did my dad looked at me and said, “I can’t do that anymore.” I smiled and said, “Well, I suppose you finally made your count and it was a good run.” He quickly interrupted me and grabbed my arm. He looked me squarely in the eyes. I’ll never forget looking into his watery cerulean blue eyes that night as he said, “You don’t understand. I can’t take a life. I can’t ever take a life again.” I was dumbfounded and completely without words. I just put my hand on his and nodded.

My dad loved animals his entire life. Even when he hunted, he treated the event as something sacred. Years ago, we were having dinner and I talked about a dove hunt I had just come back from. I made the mistake of joking that shooting from a blind out in the field was like shooting anti-aircraft weapons. He became livid with me and shook me down pretty hard for making a mockery of the hunting tradition in such a way. It really mattered to him that in all aspects of the hunt respect for the animal was imperative. It was to be treated as an almost sacred right. I’ve never forgotten that, and even though I don’t hunt any longer I still know how to advocate for a proper hunt thanks to my father.